By Aleksandra Jovanovic, Gustavo Arciniegas, Dirk Wascher – SUSMETRO

August 2024

Envision a Europe in which urban areas, the peri-urban and rural hinterlands cooperate closely on the development of food systems that are driven by the fuels of justice, inclusivity, sustainability and community empowerment. Now, imagine that such areas adopt a City Region Food System (CRFS) which offers concrete and holistic policies that improve the economic, social and environmental conditions in both urban and nearby rural areas. A food system where urban food developmental issues can be addressed and rural and urban communities can be directly linked with each other. A system in which all food actors, processes and relationships along a sustainable food chain and beyond are part of the solution in transforming our food systems – One where Living Labs play an important role in accelerating this transition.

Some food for thought, right?

Opening a conversation on what is locking city region food system transformation

As a partner organization of the CLEVERFOOD project and the wider Food2030 Connected Lab Network, SUSMETRO was warmly invited to host a co-creative session on the lock-ins, barriers and opportunities in city region food transformation during the Cities 2030 project’s final event ‘Agri-Food Justice and Policy Innovation’ that took place from June 19th to 21th 2024 in Marseille, France. Other than the event being an open space for discussing and advancing the transformation of City Region Food Systems (CRFS) through innovative policies and collaborative efforts, it was a special moment of reflection as it marked the end of Cities 2030 project.

In this session, SUSMETRO facilitated the exchange between 13 Living Labs spread across Europe and participating in the Cities 2030 project. Representing city regions from Slovenia to Spain and from the Netherlands to Norway, each living lab has their own unique stories to share on the barriers and lock-ins faced when enhancing their CRFS strategies. This cultural enrichment has also brought a diversity of perspectives on the ideas around (policy) innovation in the context of a city region food system.

First things first: what are lock-ins and barriers in a food system context?

Both lock-ins and barriers pose challenges for the positive transformation of local and regional food systems. But, what are they and what is the difference?

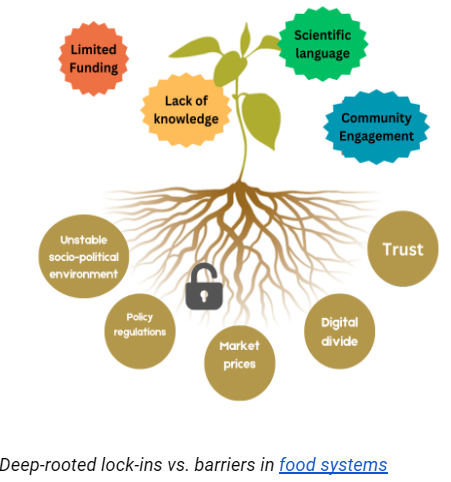

In the context of a food system, a lock-in is a deeply-rooted condition that maintains the current linear food system. These so-called lock-in mechanisms foster the status quo and ‘’develop inertial resistance to large-scale systematic shifts, as explained in this research article. Think of investments in large-scale farming, certain food policies, and food market prices. These are hard to change because they reinforce each other and keep the dominant system in place; a food regime that stimulates the mass consumption of industrially produced foods.

A barrier, on the other hand, is a specific obstacle that blocks the progress of innovative food practices, but is a challenge that can be more easily overcome. Examples are funding issues or a low public awareness on the importance of local food systems. These can be tackled directly with targeted actions with the use of an existing network of food actors.

In short: lock-ins sustain the old system, while barriers are hurdles we can overcome. So, what is needed to help unlock the sustainable transformation of the current food system and move to a more sustainable future of our regional food systems?

The co-creation session: from challenges to opportunities

The thirteen living Labs were divided into three subgroups. Each living lab eagerly shared and wrote out their thoughts and ideas on the type of lock-ins and barriers they have been facing in the context of their Living Lab activities. Below are a couple of interesting examples as shared by the living labs:The co-creation session: from challenges to opportunities

1) The food policy environment

An important lock-in recognized by the Living Labs is the current food policy environment

in European countries, which tends to slow down the innovative potential of local and regional food systems. This dominating political food economy is embedded in a productivist paradigm that promotes the mass production of standardized and ‘efficient’ food and is locking food systems in their current unsustainable trajectories.

Living Lab Haarlem (The Netherlands) gave an example of what is hampering the current food policy environment: Regarding a lock-in to food system change “CRFS is not a budgeted task for cities, meaning that the development of CRFS is not a political priority for governments and municipalities” whereas a barrier in this context is that “Food CRFS is not high on the political agenda and therefore is not seen as an alarming concern for most politicians.’’

This political environment points to a lack of awareness of politicians on the role of sustainable and regional food systems and its economic, political, and cultural significance in society. Rather than encouraging citizens to push for positive change, these obstacles can potentially feed unsustainable food choices.

2) Barriers encountered by Living Labs

Living Labs also experience internal barriers blocking the further development of their activities that aim to promote sustainable, equitable and healthy food systems.

One barrier is the lack of clarity in the role of the Living Lab’s stakeholders working on regional food system development. This goes hand in hand with time constraints and a ‘’lack of a strong business model”, which prevents the upscaling of their sustainable food innovation activities.

One thing is for sure: the lack of “long-term continuity and stable funding of Living Labs” mentioned by the Vidzeme Lab in Cesis (Latvia) and Velika Gorica Lab (Croatia) is a shared issue amongst the Living Labs.

3) Cultural and context-based barriers

Living Lab Setesdal Shop in Hovden (Norway) mentioned that “Norway being a large country with a disconnection between urban and rural areas is marking the dispersion of the food environments. This makes it difficult to bring people and food-related actors together.”

Future Food Living Lab in Bologna (Italy) touched upon a socio-political issue that hinders the development of more inclusive and just food systems: trust. The Living Lab is surrounded by communities where polarization, poverty and other socio-political challenges are present and is prioritized by the political landscape.

Trust was also referred to in a different context.The living lab from Murska Sobota (Slovenia) shared that trust was indeed a barrier to their activities. The community did not trust the blockchain-based solution brought by a technology partner, with the claim that it was difficult to understand, let alone use. Mistrust of technology was also brought up by the living lab Hovden (Norway).

In short: positive food system change is not possible without the trust and active involvement of the communities surrounding our Living Labs.

Translating the challenges into opportunities

So, in the storm of these challenges, which seeds of opportunities lie ahead to be planted into the soils of our regional food systems?

1) It’s all about building confidence

As shared by all the Living Labs, a possible solution lies in confidence building.

An example is offering training courses for Living Lab participants where management, leadership, and technological skills are further developed. With these social and technological skills, it can become easier for Living Labs to mobilize more people from the community and motivate them to engage in their activities in a more significant way.

In the context of the political food environment, these skills could be used for political mobilization and writing policy briefs to address food-related issues.

2) Consensus building

The second seed for opportunity is building consensus around a coherent and inclusive food vision for city regions. The living labs pointed to the need of food councils in city regions to coordinate the actions needed for positive change in the current food policy environment.

An example that Living Labs can be inspired by is the Belgian city of Ghent, which has been working on the topic of City Region Food System development with the launch of ‘Gent en Garde’ food policy in 2013. A food policy council (FPC) has been legally formed, consisting

of a diversity of local food system players that gives the city advice on drafting and pushing food policy proposals.

And, to serve as an inspiration to other cities: since 2018 it has had a budget to support local food innovation!

The story of the City of Ghent reflects upon the opportunity of Living Labs in being the new advocates for the development of regional food councils.

As Hovden Living Lab commented in the context of food councils: “there lies a big opportunity in creating food hubs that can connect the rural food producing areas with the urban cities.

The way forward

With the compelling stories shared by the Cities 2030 Living Labs, we have dug deeper into the experiences of Living Labs on the barriers, lock-ins and opportunities in city region food system development. Issues related to confidence and consensus building, local context, mistrust in technology and a lack of funding for the continuity of Living Labs were commonly shared by the living labs.

This session has given us ideas on how to jointly advance the transition of our food systems and promote the further experimentation with local solutions for food system transformation.

One thing is for sure, the pathway towards sustainable CRFS involves a continuous effort where Living Labs, local communities, food hubs and city food councils can be the driving force for change.

SUSMETRO also leads a Community of Practice (CoP) on Food & Health. Read here to learn more about this CoP and how to become a CoP member of a network of Living Labs dedicated to promoting the transformation of our food systems!